Let's Talk About Rejection

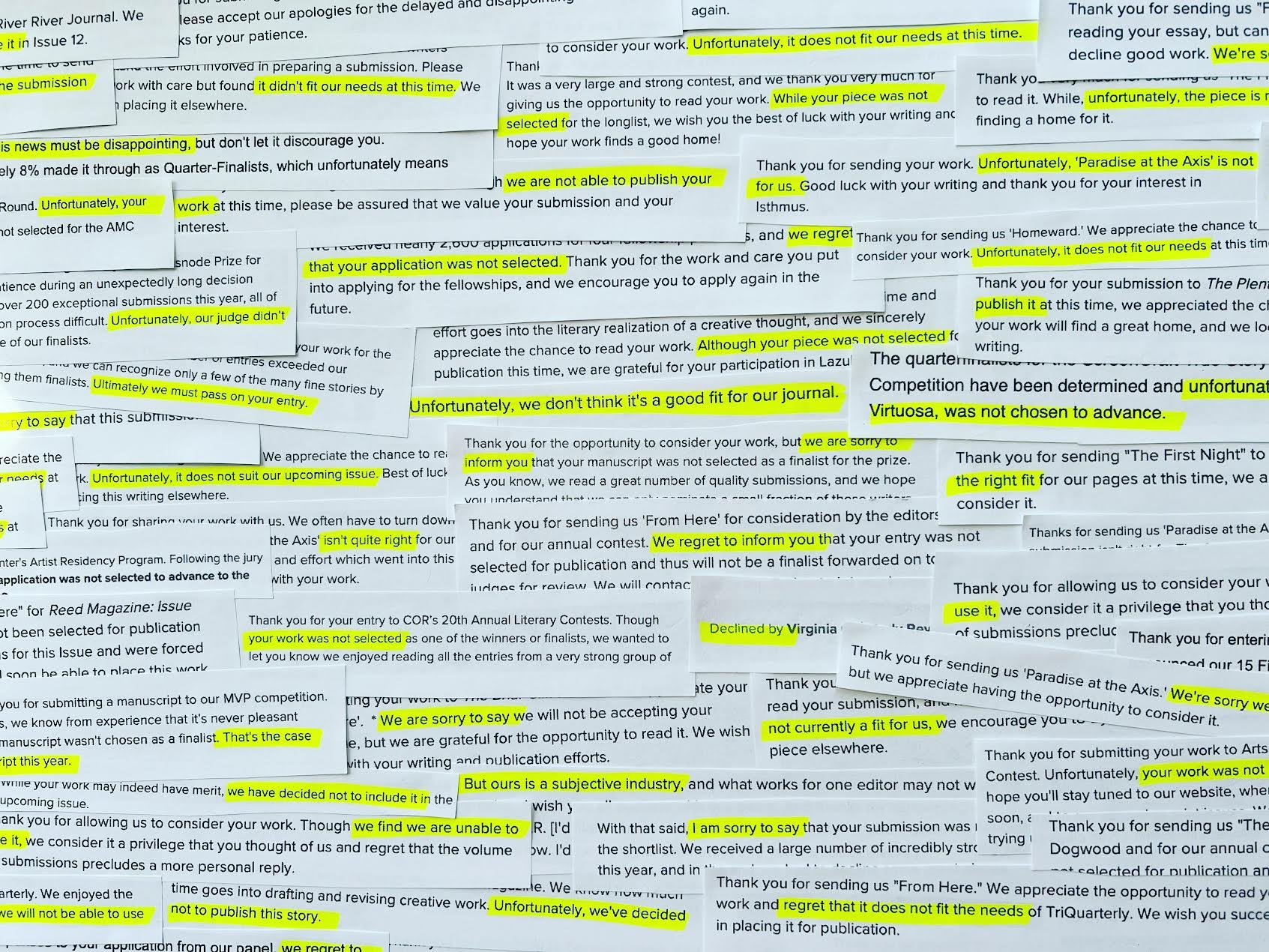

Hello, reader-creators! I made a rejections collage. Yes, a real-life collage—the kind of collage you buy a poster board and glue sticks for—of my rejections. Not all of my rejections, but the ones that were easiest for me to find through my Submittable account and old emails. (And new emails that showed up mid-collaging! The rejections never end!) I screenshotted the relevant parts of the messages, printed them all out, highlighted the most reject-y words, and assembled them all on a poster board. This took me quite a lot of time. But I wanted to write about rejection, and it felt important that I spend quality time with my rejections in order to do so.

The first thing I noticed is that rejections never say “I reject you” or “No way” or “God, you are really awful.” There is an art to rejection. Anyone who has ever gone on a couple of not-great dates is well aware of this. These are a few examples:

“Unfortunately, it doesn’t meet our needs at this time.”

“Though we didn’t select this writing for publication, …”

“Though we find we are unable to use it, …”

“But ours is a subjective industry, …”

“We regret that it does not suit present needs.”

“Unfortunately, your script did not advance.”

“While we didn’t feel it was the right fit for our pages at this time …”

“We’re sorry to say …”

See? None of them say I am an embarrassing waste of human creative energy. Most of them go out of their way to be apologetic. When you’re looking at a lot of rejections at once, trying to quickly identify the most reject-y words, you find yourself looking for the words “unfortunately,” “sorry” and “regret.” Nobody wants to reject me, these messages all seem to say, but that’s the way it crumbles, cookie-wise.

Stephen King’s novel Carrie was rejected 30 times. Vincent van Gogh was rejected basically all the time. A publisher once told Louisa May Alcott: “Stick to your teaching, Miss Alcott. You can’t write.” Rejection is part of the artist life. In fact, it’s one of the biggest parts of the artist life, but it often goes unacknowledged publicly because it’s uncomfortable. Why would anybody share on Instagram, “Here I am, rejected for the 134th time this year! Huzzah!”? It’s a little embarrassing, and we want to look good.

The thing is, I can share all kinds of fun facts about famous artists and writers and musicians who were rejected and went on to be everyone from Beethoven to Beyoncé. But that’s not super helpful to hear when you’re currently Unknown Person No. 867,933,999. Rejections can feel discouraging when you’re on a path that has no guaranteed reward at the end. What if you just keep getting rejected forever and ever and it turns out you never get recognized as the Marilyn Monroe of your generation? Maybe this is the real fear and pain of rejection—this unknown future that you’re working for, the vulnerability of putting yourself out there, the knowledge that you are not Beethoven or Marilyn Monroe and yet you are trying to make things for the world anyway, you crazy wannabe artiste. Rejection can be a painful reminder that the universe does not owe you anything, that you are one little person out of 7.96 billion people and there is only so much cultural bandwidth.

I am decently good at dealing with rejection. By that I mean, I can usually take a “no” without needing a tub of ice cream and a bed to crawl in (usually). This is in part thanks to my past life as a competitive teenage pianist whose teacher taught her some healthy attitudes toward competition. Because if you’re going to compete well, you have to have a healthy attitude about it. You have to learn to not care about some aspects of competition if you really care about making your best art (or, okay, winning). I know, being a creator is exhausting.

These are some things I find helpful to keep in mind:

It Doesn’t Matter Unless You Win

My piano teacher drilled this concept into my thirteen-year-old brain: competitions do not matter unless you win them. This means that winning a competition (or being accepted for publication, or getting a screenwriting fellowship) is not the end goal in and of itself. These accomplishments are supposed to bring opportunities to advance your art and career, and that’s the part that matters. So, if you win a piano competition and this means you get a really amazing performance opportunity, or a check to help pay for your education, that is amazing! Celebrate! But if you don’t win that piano competition, literally nothing changes. You were at neutral and you’re still at neutral. (And, fun fact, your “neutral” is the thing you can control—and you can work to make it a state that feels so much better than just neutral!) Not-winning has not brought you down. There is no opposite to winning a competition that is subjective. This is not a soccer game or a chess match. There is literally no way to “lose.”

The Chump List

This tip is more about keeping people who love you close by, because the Chump List was invented by my boyfriend. I get rejected a lot, and it’s always a pretty “meh” feeling whether it lasts a minute or a day. Every time I tell my boyfriend that I’ve been rejected (again!) he congratulates me and celebrates that we can add another name to the Chump List. His theory is that the longer the Chump List is, the more fun we’ll have looking at it once I’m wildly successful and saying, “Look at all these chumps!” (Conversely, my cat provides me with withering stares at all hours of the day, so together these two keep me decently existentially balanced.)

Own Your Rejections

Rejections are a necessary part of being an artist, so you might as well consider them a big important never-ending box to check off. Assuming you are a mortal human creator, if you aren’t getting rejected you’re probably not trying very hard. If you can train yourself to view rejections as an important accomplishment, you might be able to find a bright side to each “We Regret to Inform You.” I used to keep a list of all my rejections in a notebook so I could feel a sense of control over them. (But then I started to get so many rejections—because I was sending more stuff into the world!—that I gave up on organizing them.) Printing them out and making them into a collage is also a way to make lemonade out of lemons. Some writers may be familiar with the “100 rejections challenge,” the goal of which is to get 100 rejections each calendar year. The idea is that if you’re getting that many rejections, you are statistically more likely to get an acceptance or two—and to keep producing work either way. (Also, I believe that the more you’ve been rejected, the greater a high you’ll enjoy from a win.)

Make Yourself Teachable

I know, I know, it’s so painful to consider that maybe a piece you wrote has been rejected 56 times because it’s just not blowing anybody away. But isn’t that good to know? Doesn’t that make you want to try harder? Push your creative limits? Accept that you have to, and therefore you will, do better? Also, very rarely, sometimes rejection comes with feedback. Screenwriting contests often have a notes or coverage option when you submit your script. Getting feedback and responses from people who (usually) know what they’re talking about is a really good reason to send your stuff into the world. You’re simply not going to get a lot better without some external input now and then. Contests can give you an objective sense of where you’re at and what you should aim for next.

Your Work Is Not You

This is a difficult one for me, but you are not your work. Somebody didn’t think your story was a good fit for their publication; they didn’t make any judgment on you as an artist or a person. How could they? They don’t even know you, and they’ve only read one little thing you wrote. Keep things in perspective. A gallery didn’t select your painting to display when they had to pick just ten pieces out of the 900 that were submitted to them. You didn’t win a screenwriting contest that 4,000 people entered. Isn’t it a little silly to be sad about that?

Love More Than Fear

This is another lesson learned from my piano education. It relates more to performance anxiety, but isn’t performance anxiety ultimately a fear of rejection? You don’t have to be fearless to make art and put it into the world. You only have to love your art greater than that fear. So, who cares if you’re afraid? Focus on cultivating more love for what you do. It’s really the only thing you can control, and the only thing that can perpetually sustain you. Isn’t this great news? That you can just, you know, not even care about rejection?

For Real, Though

As I embarked on my collage-making, I worried spending a lot of time with my rejections might have a negative impact on my psyche. I was surprised to experience some positive feelings. First, once all was assembled and glued, my collage did not even look like that many rejections. I thought I was going to be swimming in highlighted “NO”s, but I couldn’t even fill the poster board I bought. This made me feel motivated to get more of them. Fill the board! Achieve more rejections than anyone before me! These rejections are barely a drop in the ocean of rejections I am capable of! Do better, Lillie!

As I read through the rejections of various prose and scripts, for the most part I remembered those drafts and I understood why they were rejected. I could recognize when I just submitted a piece way too early, and I understood when something I submitted was truly not a good fit for the place I’d sent it to. In other words: I didn’t feel bothered. The rejections made sense. Of course that work was rejected! A more beautiful way of viewing this: I incidentally made a collage of an earlier leg of my writing career, and looking at it makes me proud of how much work I have put into this, and makes me recognize, objectively, that I am now further along the path, heading in the right direction.

Finally, total demolition of your ego is not a good thing, but it is good to keep it in check. Be humbled whenever you can. It makes you work harder.

To Be Clear, Rejection Sucks

Even if you have all these tips down and you have some healthy coping mechanisms in place, sometimes rejection still hits hard. Maybe you read a rejection email right before bed, or you read it when you were hungry, or you read it right after another rejection. There isn’t usually a perfect moment where you’ve got just the right amount of energy and you’re in just the right empowered mood and you’re wearing just the right outfit in just the perfect temperature and you’re sitting at a beautiful dining table saying, “Okay, I’m now ready to accept the silver platter with my rejection!”

There’s no way around the fact that rejection is just not something we really want to experience, ever. Be good to yourself when you need it. Get the ice cream when it sounds good. Have things in place that make you feel validated, that bring you back to your art and why you make it—because the relationship between you and your art is ultimately the only thing that matters. It’s the only piece of this ever-fluctuating artist career that you can count on.

So, now I’m going to stick this poster board in the corner of a very dark closet and get back to work.

Psychologist Mark Leary has advice for dealing with rejection, and notes that “most people go through life feeling more rejected than they actually are.”

This is my go-to post-rejection song.

Finally, credit where credit is due for crumbling cookie quotes.